It’s fair to say that Jessica Jones-Supple knows her way around Woonsocket. “I grew up here, got addicted here, and now I’m doing the work here.” That work involves helping others who are living with a substance use condition as a peer recovery specialist with Community Care Alliance (CCA). Jessica is open about sharing her own journey. Despite a family history of substance use, she was a good student, earning high grades and taking college courses. However, at around age 23, she needed surgery and was prescribed an opioid pain medication upon leaving the hospital. This led to her becoming opioid dependent for about five years and resulted in her first admission to a residential treatment facility on Cape Cod. She was there for six months “but the same day I got out, I went and got pills.”

Shortly after that, her sister introduced her to heroin and she began snorting the drug. Quickly becoming addicted, she engaged in behavior that she says, “comes with the drug use,” and led to periods of homelessness, arrests and other dangerous lifestyle choices. Married with young children at the time, she says her turning point came when her husband threatened to leave and take the children if she didn’t get help.

In 2014, she went to Discovery House, which put her on the path to sobriety. “The first two years were tough. There were a lot of ups and downs,” she says. Among the “downs” was the death of her sister and her father from drug use. However, she says she was able to rebuild her relationship with her husband, children, and other family members, and to get her life back to a place of positivity.

In recovery for nine years now, Jessica acknowledges that every day is still a challenge and sometimes, a struggle. “Recovery is about learning and relearning myself. I have to recenter myself and remember gratitude.”

Jessica notes how big a part that judgment and stigma play in recovery. She despises the term “junkie”, equating it with “junk – like the people are ‘trash.’ These are human beings who still have feelings and emotions.” When doing outreach, she notes, “Sometimes, if you just take someone’s hand and offer a small kindness, it can go a long way.”

As part of her recovery efforts, Jessica became involved in Woonsocket’s Health Equity Zone (HEZ), eventually earning a stipend for her work there. With her evident passion to help others, she was invited to take CCA’s certified peer recovery course, completing it about a year ago. Since that time, she has been doing outreach in her hometown, sometimes interacting with some of the same people that she hung around and slept outside with during her years of drug use. She helped with CCA’s Safe Haven winter shelter and was recently granted the opportunity to run a NA/AA nighttime meeting group with fellow peer recovery support specialist Peter Daignault at 46 Arnold Street in Woonsocket. “Recovery is my passion. My life. I know I can’t save everybody, but if I can save just one,” she says.

With his engaging smile and upbeat personality, it doesn’t take long for Victor Lambert to win somebody over. Add in his openness about a history of substance use and you have an effective peer recovery support specialist.

A peer recovery specialist with the former Parent Support Network of Rhode Island (PSNRI), Victor says he loved his job and the work he does – especially the outreach. “I have a talent with the human connection. The people I work with in out in the community – some can be stand-offish at first but then I speak to them about my lived experience: using, being homeless – they see It,” he says.

Victor first experimented with cocaine and other drugs as an 18-year-old college freshman and then moved on to heroin, which he used for most of his adult life.

He says he doesn’t really know why he started using drugs. He grew up with a single mother, who he described as “always loving and supportive,” and two sisters in Newport. It wasn’t until he experienced the freedom of living away at college that he began dabbling in drugs that were available around campus.

A cook since age 15, he held jobs as a sous chef at many Newport restaurants. The schedule helped hide his substance use and it became costly. “I would work 70 hours a week, get a $1,200 paycheck, and then be asking someone for a cigarette the next day. It would all be gone.” He then moved to Fort Lauderdale and continued the lifestyle. “I managed, until I couldn’t anymore,” he says.

A spiral that ended in an arrest and incarceration served as a turning point for Victor. “When my sisters came to see me (in prison), they had tears in their eyes. It made me feel disgusted. I turned my life around.”

Through counseling, Victor learned how to live on a path of recovery and build his self-confidence. He is proud of what he has accomplished and has rebuilt relationships with his family. “That was precious for me.” His participation in a post-prison program led to his taking the Certified Peer Recovery Specialist (CPRS) training. “It was like I was meant for it. It was so awesome!” he stated.

Victor now worked two days a week at the former PSNRI Newport Center, hosting groups and one-on-one counseling sessions. He spends the other three days as a mobile outreach worker, talking to people and providing them with clean smoking kits, fentanyl test strips, naloxone training, and, if needed, transports to medical and recovery centers. “That’s my heart and soul,” he says, of the outreach work.

Now 48, Victor says, “I consider myself very grateful. And I really love seeing the people that I help grow.”

It’s been almost three decades, and yet Cecelia “Cece” Alston clearly remembers the moment that changed her life dramatically. She was at a house party in Providence where people were taking turns snorting cocaine. “It became my turn, and I was immediately hooked. The very next day, I stole money out of my mom’s purse to buy more,” she says.

Cece quickly went from being a young woman with dreams of being a flight attendant to a person who was constantly in need of money for her increased drug use. She was soon evicted from her apartment and then lost custody of her first child. “I lived on the street and worked the street. I lived in abandoned houses and slept in my car. Things got crazy so fast,” she notes.

During her years of using drugs, which included bouts of homelessness and arrests, Cece says she made numerous attempts to stay substance free. She estimates that she went to “10 detoxes and seven rehabs.” And each time, she went back to cocaine. “I had to get high to do everything.”

Cece noted that in most of her earlier detoxification experiences, she didn’t receive anything to aid with withdrawal or cope with the physical and emotional feelings afterwards. However, after several years of getting help at local treatment facilities, she began her long-term recovery journey. Returning to school, she eventually earned a degree in social work. “I wanted to know why I used drugs,” she said, of her quest for education.

While she doesn’t understand all the reasons for her substance use, Cece said that growing up in a rough housing development was a big factor, as was the lack of a positive male role model. While she had the support of a loving, hardworking mother, she said the loss of a beloved uncle through murder rocked the family and had a debilitating effect on her and her two siblings – both of whom also turned to drugs. “All we knew was pimps and prostitutes. We had no one to look up to,” Cece shared.

Now 27 years in recovery, Cece says she still takes life “one day at a time.” But that life is full. She is happily married and has long been reunited with her children, who are now adults. She is also fulfilled by her work as a peer recovery specialist for Community Care Alliance (CCA) in Woonsocket.

Cece says she looks forward to her job each day, where she goes out into the community to “meet people where they are at.” This means engaging in conversation, providing a snack, clothing or toiletry item, and sometimes helping someone find shelter, medical attention, or recovery support.

In her outreach work, Cece knows the importance of treating people with respect, relaying her own experiences, and overall, being “a friendly face.” However, she also notes that one of the biggest barriers to recovery is lack of affordable housing. “If someone has a place to go from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. but then no place after that, how can they get clean?” she asks.

However, Cece remains upbeat about outreach and her role in the recovery community. “I say to people, ‘You can be me, but it’s going to take work. It’s hard.’ But I believe everybody has a chance to become clean.

KAYLA’S STORY:

KAYLA’S STORY:

Michela “Kayla” Serrano provided a welcoming presence from behind the main desk at the former PSNRI’s Warwick office. As PSNRI’s former Workforce Development Coordinator, Kayla helped parents in recovery with the all-important task of connecting them to job skills training. She also provided support to those who enrolled in PSNRI’s training to become dual certified as a Peer Recovery Specialist and Community Health Worker.

Kayla, a mother of two, has been working in peer recovery since 2021, a job that she says she landed due to a “a stroke of luck.” She has held jobs in the medical field but is also a survivor of domestic violence, has experienced homelessness, and grew up with a mother who has a mental health and a substance use condition.

Kayla took PSNRI’s 70-hour training to become dual certified as a Peer Recovery Specialist/Community Health Worker. It led to a job she has a passion for and one she thinks she was called to do – encouraging and supporting others. “I love seeing the look on someone’s face when they graduate from our dual certification program,” she says.

Kayla notes the importance of the PSNRI peer recovery specialists to have “lived” experience when providing outreach and support to people who are actively using drugs or other substances and are homeless. “It’s totally different to have walked in those shoes. To understand why some people feel better sleeping in a tent in the woods than in a shelter because of the things that go on sometimes. It helps with gaining trust.”

Kayla says she loved the PSNRI community and her work with the organization, especially “the feeling that I get when I know we have helped someone.” She adds, “We cannot fill every need but we can damn sure try!”

Born and raised in one of Providence’s housing developments, Lex Morales considers that he was “always around opioids.” “Me and my siblings and cousins – all we saw was drug use, selling drugs, there was violence all around. The only resource we had was church, as a place of peace.”

Lex, who has a twin sister and five other siblings, grew up with a single mother. “She did the best she could with what she had,” he notes.

Lex says he began selling drugs at age 11 and experienced his first of many encounters with local police. Around age 13 or 14, he was sent to live with his father in Florida. However, the troubled teen soon became involved in similar drug activities, leading to an arrest and brief incarceration there.

Upon his release, Lex returned to Rhode Island as well as to his old neighborhood and lifestyle, which now included gang involvement. “Around that community, that’s all you see. Gangs provide safety, a means to make a living. There are no other resources.”

During one gang fight, he was stabbed and seriously injured. He says during this hospital stay “they pumped me full of opioids. I got addicted to them after that.” Soon he was taking a more than a hundred Percocet pills a month, although he kept his substance use hidden from his family. “I had my routine – I would take one in the morning, one at lunchtime and one at night.”

Lex says a turning point finally came for him in 2017, when, incarcerated again, he was sitting alone with his thoughts. He was struck by the number of friends and loved ones he had lost to substance use. One particularly painful loss was a cousin he was close to who died from an apparent fentanyl overdose. The cousin was found lifeless in a chair, still grasping the video controller of a game he had been playing. “That hit me because I was going to go back to that life,” he says.

Lex sought recovery treatment and through therapy and meditation sessions, plus lifestyle changes, he was successful in managing his addiction. He adds that his young son and a supportive partner are also key motivations to staying sober. “My partner is one of my biggest advocates. She is constantly encouraging me to do better – never sugarcoats anything.”

Also important was understanding why he felt the need to use. He says he thinks it was mostly to cover up the trauma of the environment he was raised in. “It was a way of numbing me from pain, tragedy. Once I learned the root of it, I learned to fight back,” he says.

However, Lex says he then encountered a different problem: finding a job as a person with a criminal record. “It was a huge barrier. I was trying to change, but no one wanted to hire me.” He eventually found work with Anchor Recovery and then Transitions Clinic but said many more recovery-friendly workplaces are needed in Rhode Island.

Lex is now employed as a peer recovery support specialist at Project Weber/RENEW (PWR), where he is also the program manager of PWR’s Pawtucket location. Additionally, he is a mentor to at-risk youth who are gang-involved and is also working to complete his bachelor’s degree in social work – with a goal of obtaining a master’s degree in public health.

Lex believes in peer outreach and harm reduction practices because, “I’ve seen it work – and in different environments: hospitals, streets, workplaces.” He also notes that for some who are using drugs “they are in that fog. The goal with harm reduction is to keep people alive enough to see their way to recovery, if they choose to.”

Lex notes that people with substance use conditions are often ignored – and they feel it. He finds that in doing peer outreach, “some people just want you to listen.” He also noted that peoples’ living situations need to be taken into account in suggesting paths to recovery – such as, if a person does not have access to transportation, perhaps they can’t take a daily medication like suboxone but they could benefit from another type of treatment.

Lex acknowledges that burn-out from peer outreach work is real. “You have people’s lives in your hands. This is dangerous work. You are exposed to situations that can trigger every day.” However, he remains hopeful about recovery work, even in those instances when someone he has been trying to help experiences a recurrence of symptoms of their substance use addiction. “People relapse, but then they can come back. “Life is learning from mistakes all the time. That’s life,” he says.

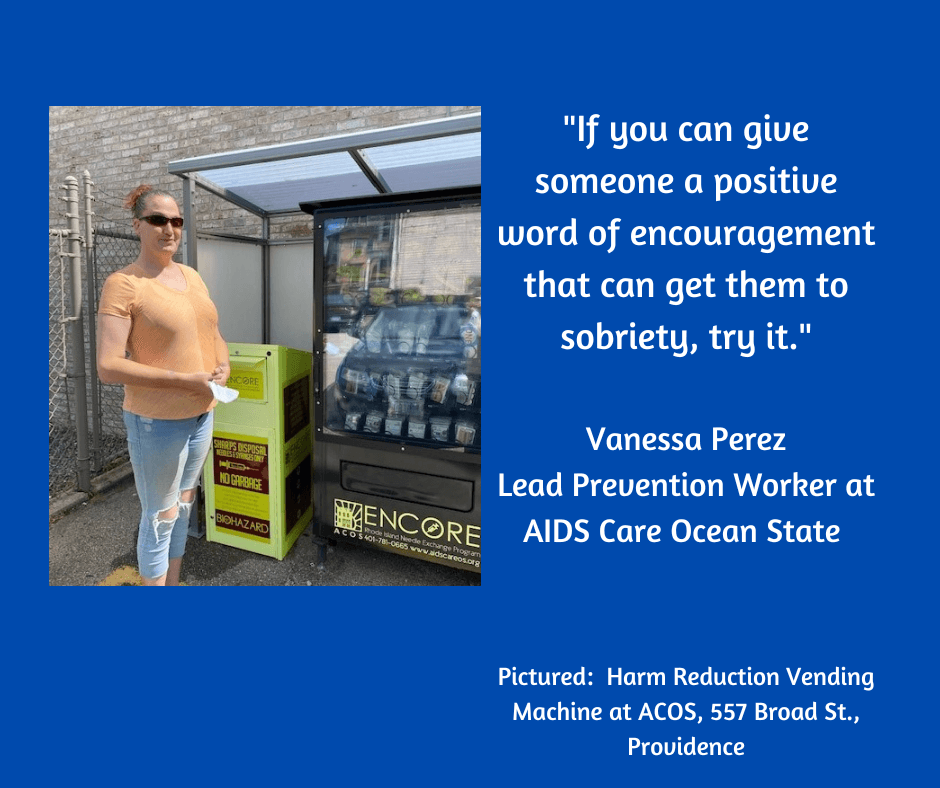

When Vanessa Perez enters a room, she seems to do it with confidence and flair, and her outgoing personality makes her a natural for outreach work. But the most important aspect of her life that allows her to truly connect with people is her experience as a person in recovery who has been living with a diagnosis of HIV/AIDS since 2007.

Vanessa began working at AIDS Care Ocean State (ACOS) in 2014 as lead prevention worker (one of many titles and “hats she wears”) at the agency serving Rhode Islanders across the state. Raynald “Ray” Joseph, ACOS’ prevention supervisor, got her involved in the organization and she credits him with the progress she has made in her recovery journey. “Ray is (and was) one of my biggest positive role models and incentives to change,” she says.

Adopted as a young child, Vanessa grew up in Cranston and had what she describes as an ordinary, happy childhood. However, she says she started using drugs at around age 25. “I think it started when I was dealing with some PTSD I experienced over my father,” she says. She lived with her biological father until age three.

Vanessa says she dabbled with other drugs (including crystal meth) but became addicted to crack cocaine, which she did for “six or seven years.” Finally, in 2017, she made the decision to seek treatment. “I finally decided that I had enough. I grew sick of the lifestyle,” she says.

Around this time, she also entered into a relationship. “I had started doing my sobriety. Then I met my husband and he gave me my reason to continue. It’s been all uphill from there,” she says. She proudly adds that she has now been “cleaner longer than I was using.”

In addition to the negative impacts on her health and well-being, Vanessa says drug use led to periods of homelessness. “I once slept under a refrigeration unit,” she says. Reflecting on those years, she adds, “If I could go back and change it, I would. But then I wouldn’t be who I am.”

In addition to encouragement from Ray Joseph, Vanessa says she decided to pursue outreach work “because I saw so many of my friends affected by drugs and go further (with their drug use) than I had.”

As an outreach worker with ACOS, Vanessa travels all over the state as part of a small team. They visit encampments where people are experiencing homelessness and other local gathering sites to talk to people and pass out harm reduction kits, which contain clean needles, fentanyl test strips, condoms, and information on treatment and recovery. At times, the work has involved hands-on rescue efforts. “There was an incident where one of our clients overdosed and we had to use nine doses of nasal Narcan to help her,” she recalls.

Vanessa is also involved in doing mobile HIV testing. “I can give someone results in about 20 minutes,” she states. If someone tests positive, she will connect them with a case manager to follow-up with information about medical treatment and other services.

Vanessa notes that she and her team sometimes run into people in the cities or towns who are critical or opposed to the harm reduction work they are doing. “A lot of community-based people are oppositional. The say they don’t want to see it on their street. Well, you may not want to see it, but it’s here,” she says.

Vanessa says she believes in the importance of peer outreach from those, like herself, who have lived experience because she has seen it work. “It’s especially important to hear from somebody who has been on the same side of the fence. It helps to have somebody who can relate.”

Peer outreach, Vanessa adds, “can especially have a positive impact when people are open to receiving the message; if my story can help to push somebody to get their mindset ready towards recovery.”

For Sheridan Duffy, being injured in a 2016 car accident in her home state of Florida led to much more than lower back pain. Prescribed Percocet from her hospital stay, she quickly grew dependent on the opioid and kept wanting more. When Percocet became hard to find, she turned to non-prescribed drugs, and within two years, was using harder substances to dull her pain.

Living with a boyfriend who was actively using drugs, Sheridan said that she stopped working and socializing with friends, ran through her savings, and “basically just stayed in the house for about two years.” Finally deciding to end her relationship, she made plans to come to Rhode Island and live with her mother and stepfather.

Sheridan said her parents had been unaware of her lifestyle in Florida. However, just a couple of hours after arriving home, she began suffering severe withdrawal symptoms. “That’s when they learned about my drug use,” she said.

Sheridan said her withdrawal was agonizing. Upon her return from the hospital, her mother and stepfather put her in touch with Tommy Joyce of the East Bay Recovery Center in Warren, RI. She credits the center with finding her a primary care physician, and helping her obtain health insurance, supplemental nutrition assistance, and other support services.

Sheridan said that for her, it was therapy that helped the most with recovery. She worked through mental anguish that stemmed from losing her dad at age 18 and other painful experiences. “It helped me to understand these things that had happened to me,” she said. She also began physical therapy and yoga and consulted a spine specialist to help with her back pain.

Any time she feels a bit vulnerable or “triggered” about drugs, Sheridan said she makes herself think back to her withdrawal and detoxification. “It lasted about two weeks – it was awful. I have to think of how sick I was. And the way your body changes when you have a clear brain. I never want to go back there.”

Through East Bay Recovery, Sheridan was assigned a peer coach and credits him, along with other staff, with helping her stay focused on her recovery journey. Now a peer recovery support specialist, Sheridan is involved in outreach work. She is planning to take on additional training to become a community health worker. “I feel that I have to give this back – what was given to me,” she said.

Outreach work involves meeting people where they are at, making a connection through conversation, and providing harm reduction supplies. Sheridan notes that no one will get help until they are ready. However, if she could offer advice to someone with substance use disorder, she would tell them to “reflect on their daily life.” “Waking up feeling sick. Having to contact dealers and then waiting for something that might take one hour, might take four hours. Is this how you want to live, day to day?

It’s such a waste of time.”

Drugs impacted Leah Carbone’s life almost from the beginning. Due to her mother’s longtime “crack” cocaine use, Leah and her siblings spent most of their childhood in and out of placements and group homes in Rhode Island’s foster care system. Her adoption as a young teenager by her middle school principal and his wife finally provided a loving home and much-needed stability. “They gave me a great life,” Leah said, of her adoptive patents. “I had a normal, happy time in middle school and they also provided me with therapy and counseling so I could deal with past traumas.”

However, when Leah was in high school, her birth mother came back into her life and she began spending time with her. That led to Leah wondering about – and eventually trying, cocaine herself. “I wanted to know what it was about this drug that made my mother feel it was more important than her family.” She started to dabble in cocaine, and then crack cocaine, and “found that I really enjoyed it.”

Leah said her drug use increased, worrying her adoptive parents. They urged her to try a rehab facility, but she refused. “I would go off on these runs,” she said. On one such disappearance, “My dad found me, and I ended up at the Center” (East Bay Recovery Center in Warren, RI). She said that her father, as an educator, had served on the Governor’s Overdose Task Force and knew of the resources available at East Bay Recovery.

Knowing how she felt about rehab, Leah noted that her parents took a different tack by just encouraging her to talk to East Bay’s Executive Director, Tommy Joyce. “I remember the first time I went to Tommy’s office, I just sat there, with my arms crossed, and didn’t say anything for about 20 minutes. And he just let me sit there. Finally, I told him that I always felt like a misfit.”

From that initial conversation, Leah opened up to Tommy about her past and her present drug use. “He didn’t judge me,” she said. Instead, he urged her to come around the center more, to meet the staff, take classes, and become involved in events, such as the annual “Rally for Recovery.”

Leah says that for her, the involvement in the recovery community center and feeling like she had found a purpose was enough to make her quit using drugs. While she takes prescribed medication for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and other health concerns, she said she didn’t rely on any medication assisted treatment to get sober. “He (Tommy) just kept me busy. That worked for me.”

More recently and now as a new mother, Leah also found meaningful employment through East Bay Recovery. After expressing dissatisfaction to Tommy Joyce about her factory job, he encouraged her to pursue training as a peer recovery support specialist. With his guidance, she successfully completed the program and went on to become a community health worker.

Leah said she loves going out into the community and doing outreach. She knows from experience that no one can be forced into recovery. “There is no pressure. We just try to start a little conversation. Ask a person if they need anything and maybe bring them a sandwich, a snack, toiletries. We just try to start a relationship first and let them know we are here.”

Leah said she is hoping to work more with people who have experienced trauma, because she feels she can provide understanding through her lived experience. “I’m really glad I came here,” she said, of East Bay Recovery.

JESSICA’S STORY:

JESSICA’S STORY: VICTOR’S STORY:

VICTOR’S STORY: CECE’S STORY:

CECE’S STORY: LEX’S STORY:

LEX’S STORY: VANESSA’S STORY:

VANESSA’S STORY: SHERIDAN’S STORY:

SHERIDAN’S STORY: LEAH’S STORY:

LEAH’S STORY: